Spring thaw in any large city is a sloppy time, grey and bleak, when the streets become the Dead Marshes of Middle Earth. As soot-stained tufts of snow bleed out into gutters, soggy bits of long-buried urban debris begin to resurface — most abundantly, most disconcertingly, cigarette butts. So, so many cigarette butts. Infinity of them. Spring thaw is when we remember, as if we ever forgot, that smoking is gross.

In today’s era of moral outrage toward everything, the act of flicking a cigarette butt onto the ground remains weirdly acceptable. Cigarette butts are definitely litter, but sometimes they feel exempt from society’s basic rules of decency. They are often cited as the most littered item in the world and are the

number one human-made contaminant in the oceans today. With 4.5 trillion of them

littered each year, leaching toxic

chemicalswhere they land, cigarette butts are a problem.

Just for fun, a term I use loosely here, on a recent weekday morning I decided to go for a walk down one side of College Street in Toronto, where I live, to count discarded cigarette butts. In the space of one block, I found 308 of them, resting in sidewalk joints, peppering entranceways. I’m not sure how many cigarette butts are too many, but 308 of

anything in the space of one block seems excessive.

I started having thoughts. Like, how did smokers get to sidestep the entire social justice movement? Why are they not getting yelled at on Twitter like the rest of us. I was a smoker once and littered with impunity, back in the 1990s, when being a good person meant using the recycling bin once in awhile. Society has changed a lot since then. Is it just less fun to shame litterbugs on behalf of the planet? Mother Nature needs to hire some millennials.

I could come up with theories about all that, but I also wanted to know where the problem came from in the first place. What are cigarette butts? Who invented them? For something so common, I knew surprisingly little.

These stubborn little things, to start, are the leftover filtered end of cigarettes. They are typically fabricated using a plastic known as cellulose acetate. According to the city of Toronto, they take

up to 12 years to biodegrade. They are a highly engineered form of trash, with a long and complicated history. And the reason they came into existence at all is actually kind of frivolous.

Imagine that cigarette filters don’t exist. You’re John Travolta, in the 1990s, and Quentin Tarantino has just revived your career. You’ve found a way to smoke cigarettes that befits your burgeoning new reputation, your fingers splayed with machismo, your face tugged into an expression of pent-up existential angst. The way you smoke is actual ballet.

Now imagine removing an unfiltered cigarette from your mouth, the movement fine-tuned for swagger, only to be left with a tuft of shredded tobacco on your lips. You meekly spit it away, but the effect has been ruined. You’re now just a schmuck. This is originally how the cigarette filter came to be: to prevent tobacco from leaking. Anyone who has rolled a doobie is familiar with this problem and usually solves it with a tiny, benign piece of cardboard. It had nothing to do with health or comfort.

In the 1920s, an industrious Hungarian fellow named Boris Aivaz

filed a patent for “smoke wads” made of crepe paper. Inserted into one end of a cigarette, they could easily prevent tobacco leakage. They were also more comfortable to puff upon than the naked end of a cigarette. Considering the ubiquity of cigarette filters today, one might expect this man to have achieved immortal fame. But nobody remembers poor Boris, because a different kind of filter, more scammy in nature, would eventually take off with the masses.

According to

Ashes to Ashes, a veritable cigarette encyclopedia by Richard Kluger, the first cigarette filter used with notable frequency appeared on Parliaments in 1931. It was made from cotton fibre and had to be inserted by hand during manufacturing. Other, more practical filters would be developed around this time, but it wasn’t until later when filters would begin to be taken seriously.

By the 1950s, sentiment was growing that inhaling the fumes of a poisonous plant, on purpose, might be a suboptimal idea. It might, actually, cause cancer. In 1952,

Reader’s Digestpublished a story called “Cancer by the Carton,” which provided solid evidence for linking cigarettes with cancer. A health scare ensued, followed by a sizeable drop in cigarette consumption.

Cigarette manufacturers had two plausible options. They could do their best to deny the evidence, or they could work toward creating a “healthier” cigarette. In what today seems like a blatant contradiction, they did both. In 1954, several major American tobacco companies ran an ad campaign titled “A Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers,” in which they attempted to refute growing evidence that smoking causes cancer.

They also began researching various filtration systems to cleanse, well,

something from tobacco smoke. As Kluger writes, tobacco companies didn’t really know what to remove or how to do it, but they tried anyway. During this time — an era eventually known as the “tar derby” — cigarette manufacturers experimented with filter after filter, each marketing theirs as the pinnacle of healthy smoking.

Kent used a filter comprised of Micronite, claiming that it offered “The Greatest Health Protection in Cigarette History.” Micronite was, it should be noted, a form of asbestos. Parliament offered a recessed filter with the reasoning that it kept tars and nicotine from coming into direct contact with the mouth. (Despite popular myth, this recessed filter was not intended for bumps of cocaine.)

Other brands, such as Tareyton, used charcoal as their magic material. In what would end up becoming the precursor of the modern-day filter, Viceroy would be the first notable brand to use cellulose acetate. Commonly, these companies geared their marketing around the dubious claim that filters made smoking — which totally isn’t bad for you — less bad for you.

None of these companies knew, of course, whether filters actually made smoking less dangerous. Certainly, the filters removed something from the smoke — tar and nicotine, mostly — but it would take decades to be able to determine whether this had any measurable effect. One thing these companies did know is that using filters helped

them significantly.

“Filter material was 15 to 20 percent cheaper than the equivalent length of the tobacco it replaced,” Kluger writes, “and the stronger-tasting leaf used to counteract the filtering effect was less costly than the milder leaf.”

In

Cigarettes: Anatomy of an Industry from Seed to Smoke, Tara Parker-Pope writes that “the rise of the filter cigarette was more a marketing ploy than anything else.” She goes on to claim that filters actually made cigarettes more dangerous by compelling smokers to inhale more deeply and take puffs more often.

This sentiment is echoed in Fred C. Pampel’s

Tobacco Industry and Smoking.“Smokers either rejected low-tar cigarettes with filters that cleansed the smoke so much as to significantly lose flavour,” he writes, “or puffed harder and longer to obtain the same chemicals from the low-tar cigarettes as from regular cigarettes.”

Others have been decidedly more alarmist. “Filters are the deadliest fraud in the history of human civilization,” Robert N. Proctor, a professor of the history of science at Stanford, told the

New York Times in 2012. “They are put on cigarettes to save on the cost of tobacco and to fool people. They don’t filter at all. In the U.S., 400,000 people a year die from cigarettes — and those cigarettes almost all have filters.”

Today, it is pretty much universally recognized that filters don’t really make smoking safer. Still, filters rose to popularity on a premise of health and wellbeing, and people fell for it. As Parker-Pope reports, filtered cigarettes surged from less than one per cent of the market in 1950 to 87 percent in 1985. Today, almost all cigarettes on the market are filtered.

So it appears we were collectively duped into adopting a faulty technology that is now posing a somewhat remarkable environmental threat. But where does this leave us? Are we just doomed to drown in cigarette butts?

The solution seems obvious: we should just be smarter with our butts. Put them out, all the way, and throw them in the garbage. Some smokers have even been known to carry around

portable ashtrays, which seems mighty courteous, though not very convenient.

But there is an irony here. A lot of smokers just don’t seem to care. I mean, that’s part of the appeal, right? Lighting up to demonstrate your complete ambivalence toward consequences? Then again, why use filters at all if you don’t care? This whole thing is just a series of contradictions.

The future may not be so bleak, though. For one thing, as

USA Today reports, cigarette smoking has hit an

all-time low among adults. Vaping is viewed as a better alternative, which is not an automatic silver lining, but it does seem likely to generate less cigarette butt waste.

Increasingly, some forward-thinkers are figuring out ways to recycle cigarette butts into usable products. According to news aggregation site

ScienceDaily, one team of scientists in South Korea “successfully converted used cigarette butts into a high performing material that could be integrated into computers, handheld devices, electric vehicles and wind turbines to store energy.”

Terracycle, a waste management company that re-uses traditionally non-recyclable items, uses cigarette filters to

create a variety of industrial products, including plastic pallets. Meanwhile, in Europe, crows are being

trained to collect and dispose of discarded butts — a difficult feat, apparently, for humans.

This whole problem is symbolic of many things. Our gullibility, for one, but also our laziness and our tendency toward self-destruction despite countless warnings. Like, maybe mass marketing campaigns from large corporations should be viewed with a bit more skepticism? Probably, we just need to care a bit more. About everything. Just a little bit more. Because with the path we’re on, the Dead Marshes of Middle Earth might be closer to our backyards than we think.

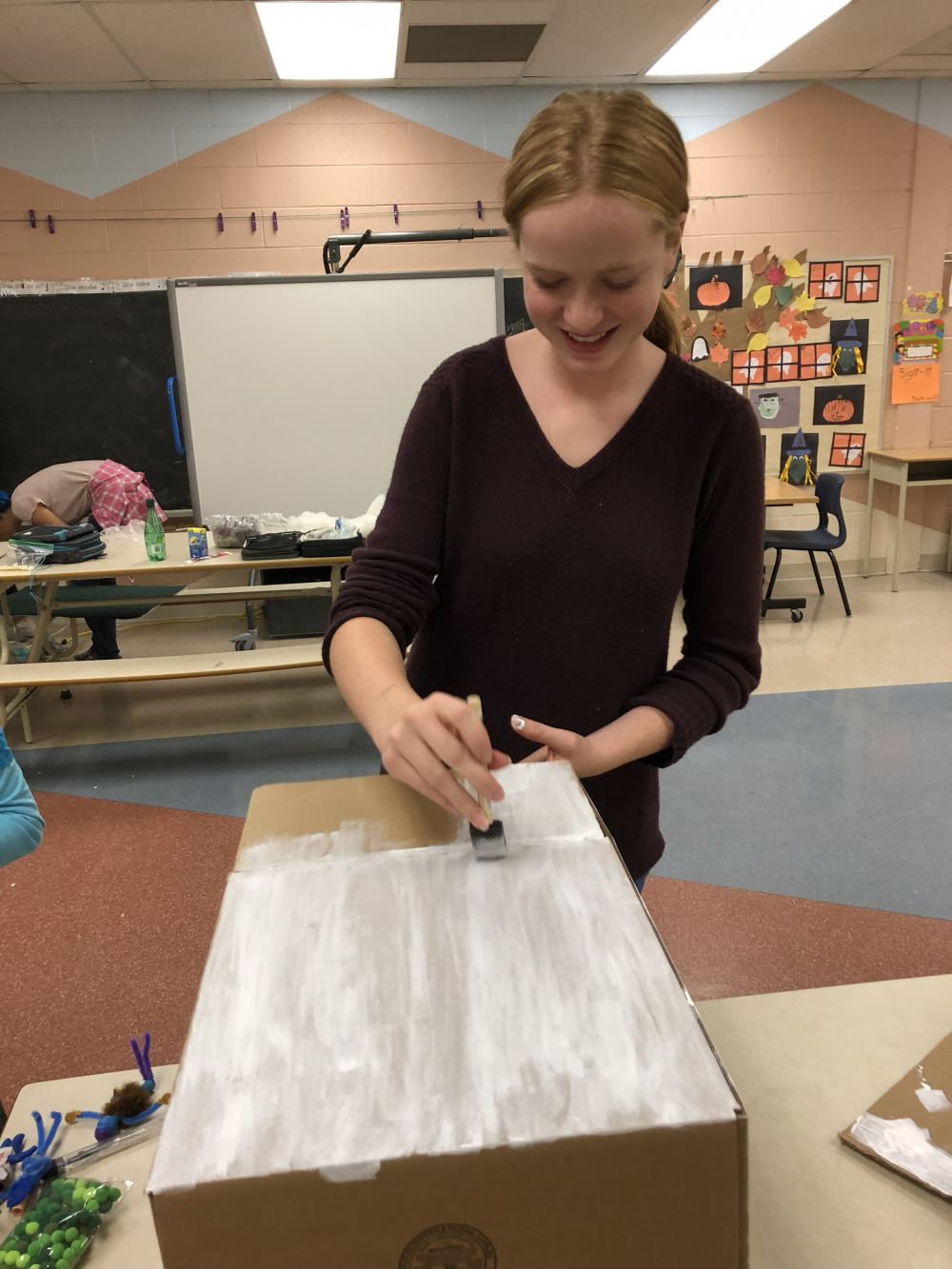

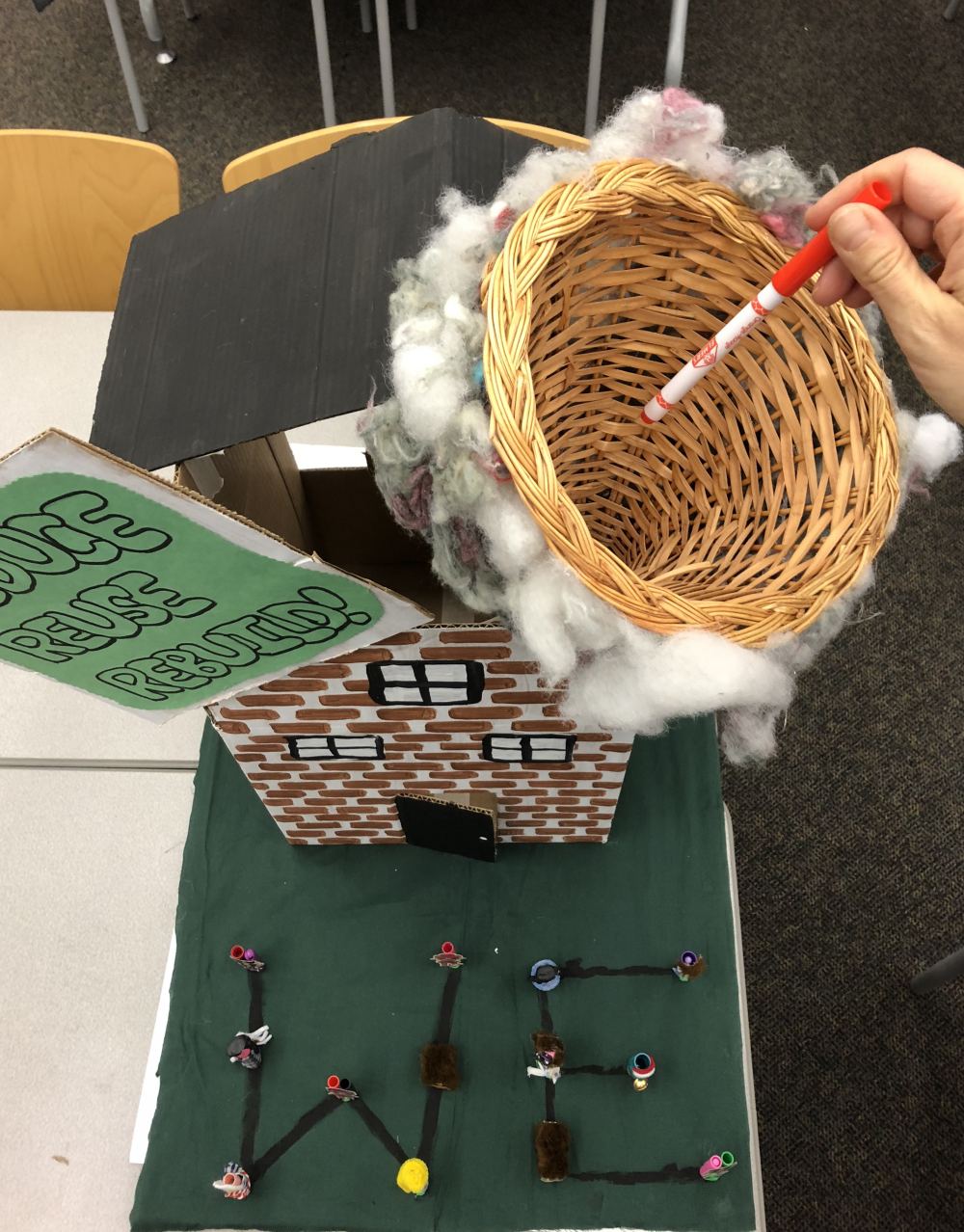

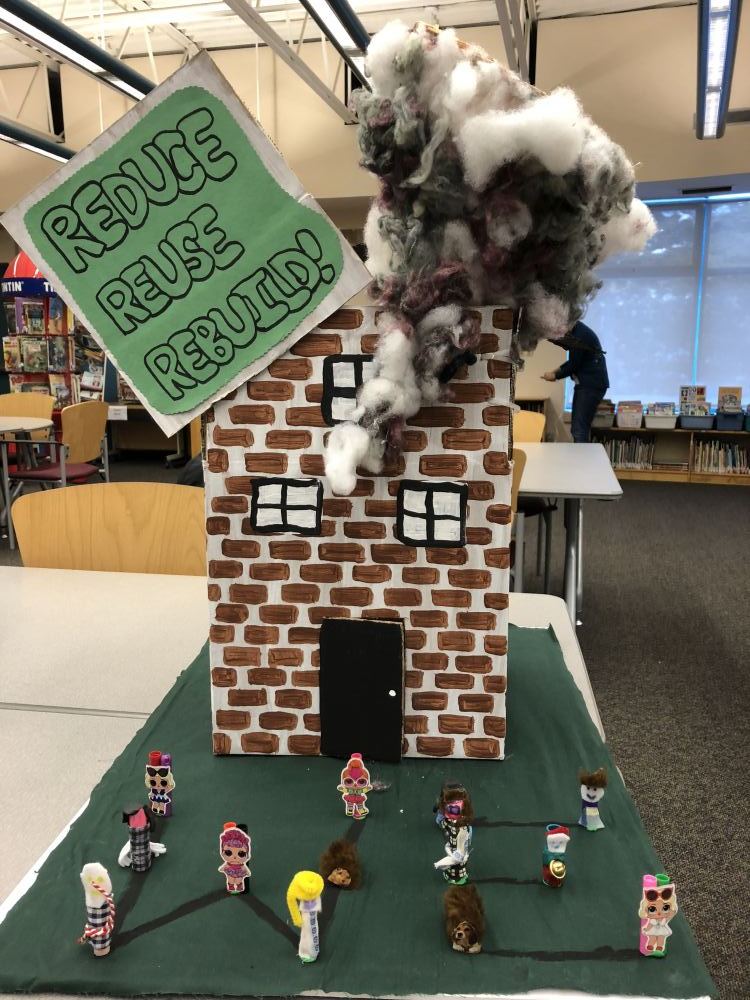

A. Lorne Cassidy Public School, of Stittsville, enthusiastically entered the contest.

The students used their creative talents to develop and construct their project using their recycled writing implements and this was submitted for consideration to the contest. A. Lorne Cassidy students and teachers are pleased to announce that the school has been chosen from entrants across Canada as one of the top finalists in the #8 position.

Karen Swerdfeger, a parent volunteer, said, “we found out about the contest as our school registered with Terracycle (who partnered with Staples for the marker recycling and contest) last year when we learned what they do and how it can lead to fundraising for our school. But most importantly, we wanted to bring the marker recycling initiative to the school. Last year was the first year we collected markers.”

She went on to say, “entering was as simple as submitting two pictures and a small blurb on the kid’s creation. I wish I could tell you what it took to get this far but it was not transparent. I got a blanket email today about voting and saw the kid’s box!”

A. Lorne Cassidy Public School, of Stittsville, enthusiastically entered the contest.

The students used their creative talents to develop and construct their project using their recycled writing implements and this was submitted for consideration to the contest. A. Lorne Cassidy students and teachers are pleased to announce that the school has been chosen from entrants across Canada as one of the top finalists in the #8 position.

Karen Swerdfeger, a parent volunteer, said, “we found out about the contest as our school registered with Terracycle (who partnered with Staples for the marker recycling and contest) last year when we learned what they do and how it can lead to fundraising for our school. But most importantly, we wanted to bring the marker recycling initiative to the school. Last year was the first year we collected markers.”

She went on to say, “entering was as simple as submitting two pictures and a small blurb on the kid’s creation. I wish I could tell you what it took to get this far but it was not transparent. I got a blanket email today about voting and saw the kid’s box!”

First prize is a chance to win two outdoor garden beds and a picnic table made from 100% recycled plastic, as well as a $1,000 donation to any school or non-profit organization of choice, along with a $300 cheque for garden supplies. The students have decided to donate any winnings to the Dunrobin Tornado Relief Fund.

In order for A. Lorne Cassidy students to be awarded the top prize and able to donate to Dunrobin, they are asking everyone to vote for photo #8 before December 28, 2018 at the link below:

First prize is a chance to win two outdoor garden beds and a picnic table made from 100% recycled plastic, as well as a $1,000 donation to any school or non-profit organization of choice, along with a $300 cheque for garden supplies. The students have decided to donate any winnings to the Dunrobin Tornado Relief Fund.

In order for A. Lorne Cassidy students to be awarded the top prize and able to donate to Dunrobin, they are asking everyone to vote for photo #8 before December 28, 2018 at the link below: