Packaging: A $1.2 Trillion Sector Going Through a Rethink

We’re Asking a Lot More of Packaging Than We Used To — and Suppliers Are Responding

As e-commerce continues its penetration into every corner of our commercial lives, the packages that land on our doorstep have a lot more work to do than ever. The massive amounts of packaging that have accompanied the digital revolution and a surge in single-use products such as Starbucks coffee cups are starting to draw critics’ attention.Out With Analog, In With Digital, and Not Just for Replacing Printing

Although digital technologies for producing labels and other printed messages on packaging containers have been around for some time, the last few years have seen an inflection point in producers’ preferences. Sales of conventional analog “flexo” printers have been declining, while sales of digital printers are enjoying double-digit growth. As it does in many other industries, digital is enabling entirely new kinds of connections with end users by making small print runs affordable. One outcome is a rise in the amount of personalization that organizations can offer and that consumers increasingly expect.Even more important, brands are beginning to leverage digital technologies that enhance and extend the reach of their packages well beyond the actual package. A great example of this is Coca-Cola’s successful Share a Coke campaign, launched initially in 2014. The campaign involved replacing the Coca–Cola logo on bottles of the beverage with popular American first names. Consumers were encouraged to find bottles with their own names or those of friends or family members, then post on social media about their experiences, using the hashtag #ShareACoke. The promotion took off to the point at which Coca–Cola not only expanded the numbers of names on bottle packaging, but today allows customers to order customized bottles with names on them from the Coca–Cola store. Customers reportedly shared over 500,000 personal stories with the hashtag in the first year alone. Beginning in 2018, stickers with the names were used on the packaging, expanding the reach of the name to, well, anything you could stick it to!

Coke is adding a new digital element to its packaging with a program called Sip and Scan™. Users either go to Coke.com or use the brand’s mobile app to capture a photo of an icon that allows them to access treats and enter competitions for prizes. Among these are concert, movie, amusement park, and baseball tickets and exclusive experiences like meeting members of the US Women’s National Team (USWNT) after the FIFA Women’s World Cup. Of course, the company gets some goodies for itself as well — namely a direct connection to users’ phones, location, and purchase history — a data goldmine.

Not to be outdone, Coke’s arch-rival Pepsi has a few twists on packaging of its own. One was the launch of “Snackable Notes” — packaging for Frito Lay’s variety packs (Cheetos, Doritos, Lays, and a host of other brands). The packages left a blank space for parents or others to write notes right on the bags. Targeted for the anxious back-to-school months, the blank spaces on the bags are not only meant to encourage people to connect, but to post on social media as well, under the hashtag #snackablenotes of course. The company also launched a donation campaign as well — for every note posted, it contributed to Feed the Children.

Shapes Nature Never Designed — Flexible Packaging on the Rise

With advances in materials, it’s now become possible to use flexible packages — pouches, wraps, bags, envelopes, and many more form factors — instead of rigid boxes or cans. Flexible packages allow brands to indulge consumers’ desires for re-sealable, easy to carry and store, lightweight packaging to complement on-the-go consumption. Manufacturers are figuring out how to use flexible packaging to help with the reduction of food waste, carbon footprint, and shipping damages in a variety of formats that go beyond bottles and cans.And of course with headlines screaming that millennials don’t even own can-openers, some kind of alternative to the reliable can of tuna fish is going to be necessary.

Meanwhile, not all innovations in packaging are welcomed by those who want to get at the goods inside. I was startled to learn that the term “wrap rage” is actually a thing, if Wikipedia is to be believed. This stems from a fundamental disconnect — what works for the manufacturers of packaging can make it well-nigh impossible for ordinary people to get at the contents. Over the counter drugs have to show tamper-resistance. Some packages are deliberately designed to prevent access to limit shoplifting. And others are more about showing the potential customer what is in the contents than actually helping them to access the contents (hard plastic blister-packs, we’re looking at you!). The clamshell package is among the most dangerous, as it is designed to be unable to open with bare hands, resulting in some 6,000 emergency room visits in the US alone each year and thousands of more minor injuries.

An innovator in this space is Amazon, which launched its Amazon Frustration Free Packaging initiative in 2007. The idea is to create packages with less waste, that don’t require additional boxing, and which are easier for consumers to open. Vendors apply to be certified and are offered incentives to join the program, which Amazon claims to have used to save 244,000 tons of packing material in the 10 years since it launched.

Moving Toward the Circular Economy?

I’ve written before about Tom Szaky, the former Princeton student who founded Terracycle with the mission of eliminating waste. The company got going by using the university’s cafeteria waste to farm worms, then selling the…um…product as fertilizer. “Worm poop” was a memorable way to describe what the company did in its early days. Szaky has recently edited a book that takes the “no waste” manifesto directly to packaging. Called The Future of Packaging: From Linear to Circular, he seeks to replace the one-way take-make-waste process of packaging with a circular design, drawing the analogy to skins that protect fruit but which can be easily recycled.Manufacturers of edible packaging have taken a page out of Szaky’s book. In what I can only think of as a bid to introduce a mature brand to a whole ‘nother generation of consumers, Glenlivit has introduced whiskey pods to the market. Yup, think laundry detergent pods except with a whiskey cocktail inside. The capsules, Glenlivit has told a skeptical public, are made from edible seaweed — just pop them in your mouth — no glass, bottle, or stirrer required. The packaging is made by Notpla, a new entrant in the biodegradable packaging world. Unhappily for those of us who wanted to give the cocktail pods a spin, they were sold on a limited time-only basis.

Edible and biodegradable packaging, however, is making its way into more mainstream products. We have straws you can eat (Sorbos Ecostraws), spoons you can eat (Bakeys), decomposable cups to replace plastic ones (Loliware), and even Poppits toothpaste pouches, which are single-use “servings” of toothpaste designed to eliminate messy tubes. Still more important, major brands are beginning to get on the circular packaging um…bandwagon. Unilever, in a move that is sure to put pressure on its consumer packaged goods rivals, just recently made headlines with an announcement that it plans to halve its use of new plastic by 2025. The company plans to use so-called naked packaging (how exciting) for some of the reduction and replacing non-recyclable packaging with the recyclable kind for the rest.

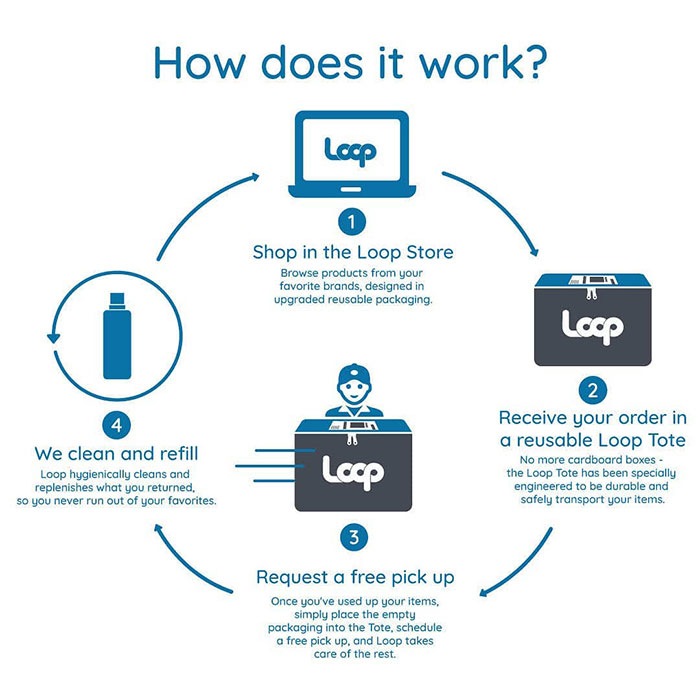

Among the more interesting innovations emerging from the concern over packaging waste is the Loop ™ system being piloted by a consortium of brands, inspired by — you guessed it — Tom Szaky, who used the World Economic Forum meetings in Davos to talk leaders of major multinational brands into supporting the idea. Combining a digital platform with a completely different approach to packaging, the system echoes the return of the milkman, as an observer pointed out. The idea is that consumers place orders online for products from trusted brands, which are delivered to them in purposely-designed refillable containers. When the product is used up, the consumer returns it to the Loopstore, which it gets refilled and re-delivered. I have to say, the thought of getting brownie mix and Ranch dressing in re-usable containers has a certain appeal.

Who knew that the world of packaging had so much going on!